Mati Diop's award-winning documentary 'Dahomey' chronicles how the return of stolen African artifacts reflects a larger identity crisis

In 1892, French soldiers looted a number of totems and treasures from the West African kingdom of Dahomey, considering these items the spoils of victory after winning the Second Franco-Dahomean War. For over a century, the items sat in French museums, watched over by French security guards and viewed primarily by French citizens. In November of 2021, President Emmanuel Macron okayed the return of 26 artifacts to the nation, now known as Benin. The country was “generously” given back a small part of their stolen history. It was viewed as a victory for the former colony, though what this gift might mean for its modern-day citizens was anybody’s guess. For the artifacts themselves, it was somewhat of a bitter homecoming, returning to an unrecognizable place after being “cut off from the land of my birth, as if I were dead.”

That these statues of long-dead royalty and other objects of worship get to voice their own thoughts and feelings regarding this belated mea culpa is simply one of the many amazing things that Mati Diop’s Dahomey adds to this chronicle of reclamation. It’s a magical realist touch that turns the journey of these plundered goods into something like a first-person narrative, as a wooden and metal likeness of Benin’s King Ghezo — the artwork refers to itself as “No. 26,” a.k.a. the name listed on the inventory — frets over relocating to a land in which he has little memory and even less context. He’s a self-admitted emblem of a past that he fears holds no appeal or sense of significance to the present. Diop, however, wants to remind us all that time is a flat circle. Even the documentary’s name is a callback, an echo designed to reiterate that we might be done with the past, but the past is never done with us.

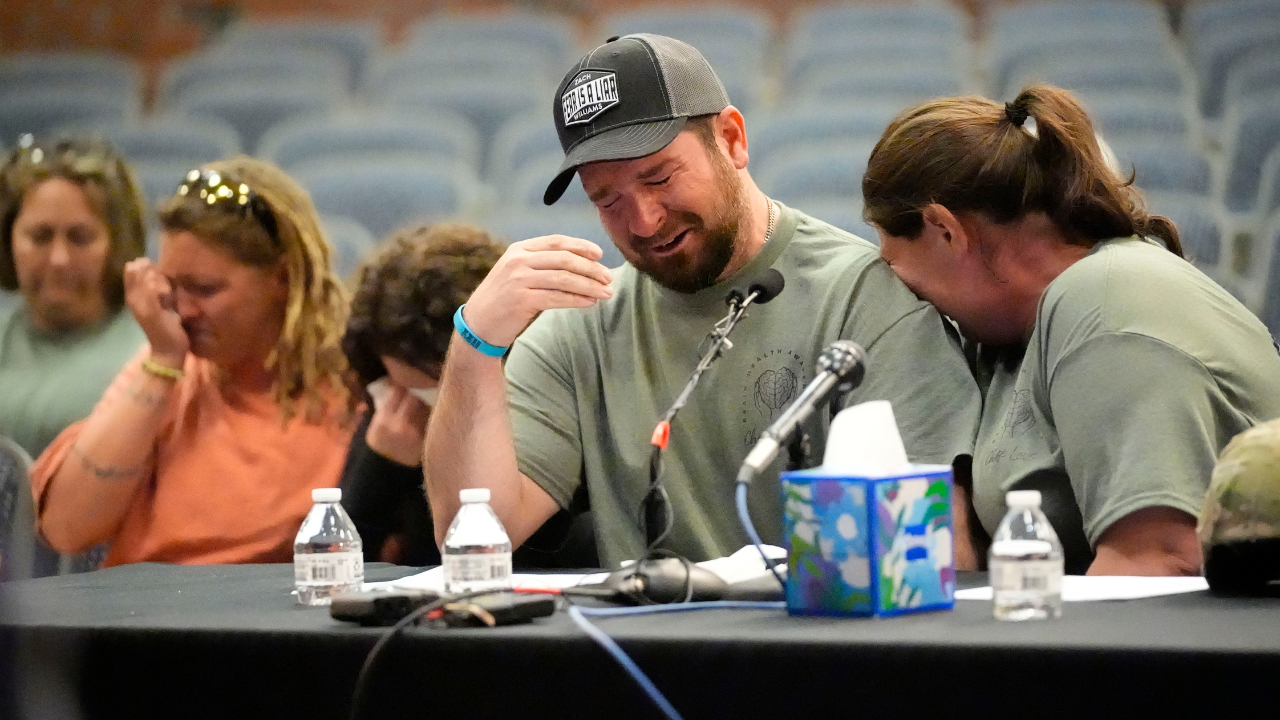

A French-Sengalese filmmaker whose 2019 feature debut Atlantics immediately earmarked her as a filmmaker with a keen eye and a knack for blending the natural and the supernatural, Diop mixes these baritone musings from No. 26 with straightforward vérité of workers boxing these objects up, the parade thrown in honor of their return to Benin and the patrons who silently view these symbols of a thwarted legacy. We get to see everyone from construction workers to children reconnect, or at least attempt to reconcile, with their own history.

Trending

Editor’s picks

Most importantly, however, she trains her cameras on an extended debate held between students at the University of Abomey-Calavi about the bigger picture of it all, which is where Dahomey enhances its documentation with dialectics. A speaker notes this is less about their country and more about France “rebranding” its image by appearing to be simultaneously charitable and magnanimous. Another calls the entire thing an insult, given that only 26 out of 7,000 items were returned. The entire concept of a museum is indicted as a Western institution which, in the words of one young man, reduces holy items and sacred imagery to mere “stuff.” The hearts and minds of a generation have been won over and molded by other means in the absence of these signifiers. “I grew up on Disney, Avatar, Tom & Jerry,” notes one twentysomething. “I didn’t grow up watching an animated movie on [Dahomey’s King] Béhanzin.” Another expresses it in the most cut-the-crap way possible: “What was looted 100 years ago was our soul.”

What happens to a country’s cultural heritage when the elements that once defined it are taken away? Does the giving back of such things heal the original wound, or just reopen it? Who owns a colonized culture — the colonizers, or its original creators? These are questions that Dahomey, in a mere 68 minutes, attempts to tackle in the most engaged and lyrical manner possible, and what it lacks in answers it makes up for platforming the notion that such things still urgently need to be discussed. You get the sense that France might view their generous offering as the conclusion of the conversation. This doc — easily one of the best and most modestly brilliant piece of nonfiction filmmaking you’ll see this year — counters that it’s merely the beginning. There’s a much larger dialogue to be had about accountability and the damage done. Thankfully, Diop gives her narrator No. 26 the last word: “I won’t ever stop.”

2 hours ago

1

2 hours ago

1

.png)

.png)

.png)

.png)

English (US) ·

English (US) ·  Hindi (IN) ·

Hindi (IN) ·